“Hot or Cold” at Laodicea

A common myth regarding Laodicea has to do with Jesus’s statement to the church there, “I wish that you were hot or cold; because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of my mouth” (Rev 3:15-16). The misconception is that this figure of speech is based on water supplied to Laodicea from the hot springs at Hierapolis and the cold springs at Colossae.

Example of a misguided graphic implying that Laodicea received its water from Hierapolis and Colossae.

The Romans mastered the construction of aqueducts to bring large amounts of water to cities, but water was never brought to Laodicea from either Hierapolis or Colossae, and here’s why.

Hierapolis Water Was Not Potable. The hot springs at Hierapolis were so saturated with calcium carbonate that they produced a beautiful series of unique travertine pools where they flowed down the hillside below Hierapolis.

Even in the 1st century the waters were valued for their healing powers, but this involved bathing in the waters, not drinking them. Although small amounts of calcium carbonate can act as an antacid, excess amounts can cause hypercalcemia and digestive issues. Also, from a practical perspective, water with this much calcium carbonate would have quickly plugged any aqueduct channel through which it flowed.

There Was No Aqueduct From Hierapolis to Laodicea. If an aqueduct had ever been built from Hierapolis to Laodicea, there would be some evidence of it. Furthermore, it would have been the most impressive Roman aqueduct ever built! The distance from the springs at Hierapolis to Laodicea is approximately 6 miles. Roman aqueduct systems were regularly this long and longer, but not over an open expanse. Aqueducts typically followed the terrain to minimize the work required. If necessary, the channel could cross a canyon on a bridge, or even a plain on a series of arches known as an arcade. The longest known arcade is part of the Zaghouan aqueduct that fed Carthage in North Africa, stretching 6.9 miles. At it’s highest, though, this arcade is only 65 feet tall.

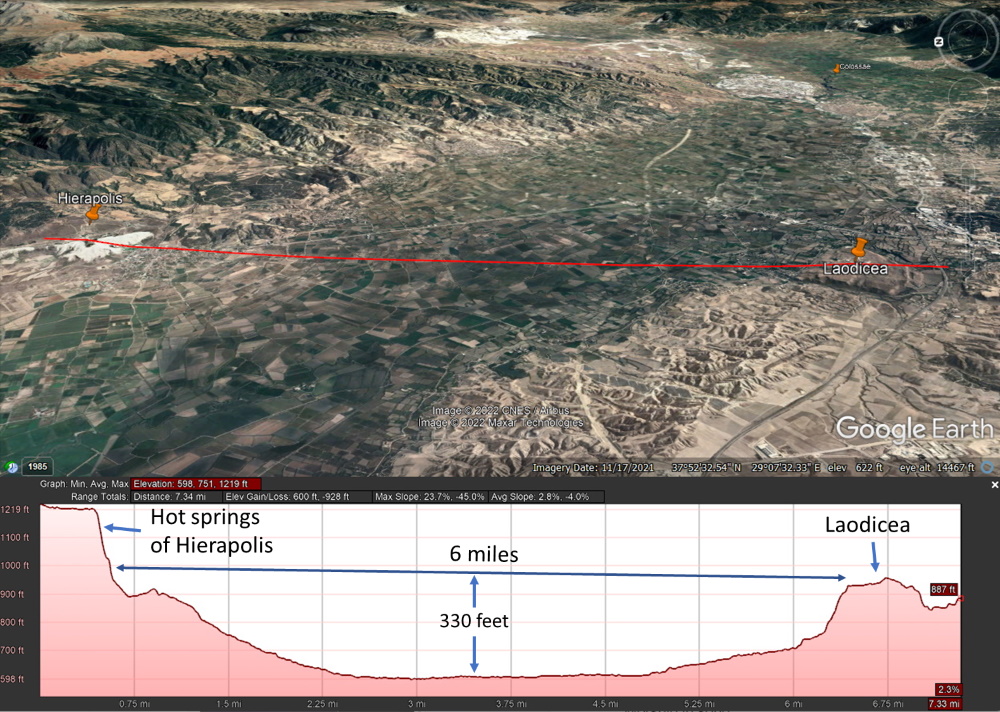

By contrast, a hypothetical aqueduct from Hierapolis to Laodicea would need to cross 6 miles, but at a sustained height of over 330 ft!

Google Earth view of a hypothetical line from the hot springs at Hierapolis to Laodicea, with an elevation profile.

The white travertine pools of Heirapolis/Pamukkale are easily visible from Laodicea on a normal day. This photo shows the view toward Hierapolis from the large theater on the north side of Hierapolis. The travertine terraces of the hot springs at Hierapolis/Pamukkale are visible as a white splotch across the valley. Imagine the magnitude of an aqueduct bridge that would span this distance at eye level!

View of the travertine terraces of the hot springs of Hierapolis, from the north theater of Laodicea. Photo by Todd Bolen, BiblePlaces.

The tallest known Roman aqueduct bridge is the Pont d’Ael, in northern Italy. This bridge carried water 216 ft above the canyon floor, but the bridge is only 198 ft long from end to end, making it taller than it is wide.

The better known Pont duGard is 899 ft long, and 161 ft tall. It is an impressive bridge, and one of the best preserved Roman aqueduct bridges, but it pales in comparison to the bridge that would have been needed to bring water from Hierapolis to Laodicea. An aqueduct bridge from Hierapolis to Laodicea would have needed to be more than twice this tall, and 35 times as long!

The Romans sometimes used an inverted siphon to cross valleys, allowing them to use a reduced height bridge system. The problem with this kind of system was that water pressure became an issue as the height increased. In fact, such a system was used at Laodicea to cross the short saddle between the city and the hills to the south, but it was a relatively short and shallow siphon. It was made of large blocks of limestone, each with a hollow center, that were fitted tightly together.

Section of the double inverted siphon at Laodicea, as it bends to go down the hill to the south; photo by Todd Bolen.

Though I agree that it does not refer to aqueduct water, the location and the fame of the two of the three triplet cities in the valley would have immediately brought to mind the fame of the healing hat springs of Hierapolis and the crisp fresh drinking water of Collosae and the rivers 6 miles away, contrasted with the fact that with all their wealth in the city, it had no private water source and they were forced to bring in water from outside, but that water could not be drank due to the clay pipes and the desert it needed to cross.

So the message would be clear… I wish you were USEFUL for ANYTHING but you are depending on outside sources for your blessings, and a useless Christian is of no value to the work of ministry.

I would contrast it with Jesus telling the Samaritan woman that if she drank from Jesus’ waters, then it would become a spring of well water IN HER!

In other words.. .you dont refresh, you dont heal, but your water is outsourced and outsourced water is undrinkable and good for neither healing nor refreshing.

It also seems confirmed in the comment that they are not even in fellowship with Jesus who WANTS to share meals with them but they wont let him in. No personal source of spiritual usefulness, just selfish dependence on the blessings from others.

Excellent

Thank you Pastor Robert

This comment really helped me understand better

I agree. While I appreciate the historical information provided in the article, I don’t think it was necessary to make the leap to beverages at a meal. Thank you Pastor Robert, as a laymen, I was struggling with this conclusion.

Robert, thanks for your thoughts on this. For the sake of clarity I would point out a few problems that I think exist in your analysis. One is that you begin by agreeing that the reference is not to aqueduct water, but then you suggest that it refers to “outsourced” water because Laodicea “had no private water source.” The fact is that the only way to get water to any city (assuming there was not a large spring within the city walls) was to use an aqueduct. To say that “it does not refer to aqueduct water” but then turn around and say it refers to “outsourced water” is self-contradictory. By the way, most large cities in Asia Minor (as throughout the Roman empire) used aqueducts to bring in water. Ephesus brought in water from at least 4 different springs, as did Pergamum, and dozens of smaller cities like Miletus, Priene, Aprhodisias, Tralles, and Smyrna all used aqueducts to provide fresh water to their inhabitants.

I’m also curious about the statement, “they were forced to bring in water from outside, but that water could not be drank due to the clay pipes and the desert it needed to cross.” To which desert do you refer? I’m not aware of any desert in that region. Also, how did clay pipes negatively affect drinkability? Clay pipes were not used until the water got to the distribution center inside the city. The aqueduct itself was constructed of stone. Finally, if “that water could not be drank,” why was the aqueduct built in the first place? The Romans were experts at bringing potable water in to a city from long distances; in fact, it was critical to the growth of large cities throughout the empire. Would you suggest that whoever built the aqueduct system that supplied Laodicea failed in some way to provide water that was potable?

In the context of 1st century Asia Minor, it seems that Parker’s suggestion regarding how they viewed different temperatures of drinks (with lukewarm being used to induce vomiting) is a much better fit than the idea that it refers to water that came through an aqueduct (“outsourced” water).

Thank you for this explanation.